When DC artists come home for one of the city’s 3-H summers (hot, hazy and humid), you gotta jump on them and ask, “Why?” It’s like following Harriet Tubman south instead of north. That’s not the pattern for a DC born artist. “Go to New York, LA, Europe. Come back when you’ve made it, when the President invites you to the White House, or your momma or daddy needs you at their sick bed.”

When DC artists come home for one of the city’s 3-H summers (hot, hazy and humid), you gotta jump on them and ask, “Why?” It’s like following Harriet Tubman south instead of north. That’s not the pattern for a DC born artist. “Go to New York, LA, Europe. Come back when you’ve made it, when the President invites you to the White House, or your momma or daddy needs you at their sick bed.”

But Thomas Sayers Ellis came home to DC and he’s taking some of the goods back with him.

I was introduced to Ellis’ work via the internet, mainly through E-Notes, and finally got a formal introduction at this year’s Smithsonian Folklife Festival where he was a guest artist for the “Giving Voice: The Power of Words in African American Culture” exhibit. He had his camera on him.

Thomas Sayers Ellis was born and raised in DC. He took inspiration from DC’s Go-Go music scene, its percussive and poetic pulse. He attended Paul Laurence Dunbar High School. Ellis co-founded The Dark Room Collective in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1988, and earned a M.F.A. from Brown University in 1995. His work has appeared in many journals and anthologies, including Poetry, Grand Street, Tin House, Ploughshares and The Best American Poetry. He has received fellowships and grants from The Fine Arts Work Center, the Ohio Arts Council, Yaddo and The MacDowell Colony. Sayers is a contributing editor to Callaloo and Poets and Writers. His first, full collection, The Maverick Room, was published by Graywolf Press in 2005 and awarded The 2006 John C. Zacharis First Book Award. He is an assistant professor of Creative Writing at Sarah Lawrence College and a faculty member of The Lesley University low-residency M.F.A program (Cambridge, Massachusetts).

You can read his articles and see more at his website genuinegro.

E916: When I emailed you, I asked if you’d share with my blog readers what you did during your summer in DC. A clichéd question, but nevertheless, to the point. Being that you’re a DC native and an artist–poet, photographer, journalist and you can fill in the blanks on the rest–who resides in Brooklyn, what brought you home for the summer? Is DC still “home”?

TSE: I walk during the summer, strolling humidity. I invent things like statues.

I am looking for a place to put a Statue of Sterling Brown and not at Howard University either, some place kids can climb it and say who was that old man and have his just be an old man. The city is change and I walk to witness it, to prevent it, to record it.

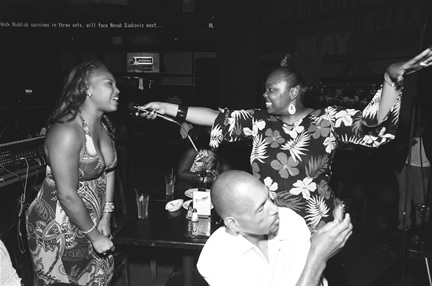

I write early in the morning and then I walk and take pictures for my project The Go-Go Book: People in the Pocket in Washington. I carry old Go-Go records and a poster around and beg strangers to let me photograph with them. At night I am usually at some band’s practice or at a show. I do Go-Go weddings and Go-Go funerals too.

DC is still home; it carries me. I carry it despite the fact that I saw two gentrifiers kissing their dog in the mouth in Columbia Heights.

E916: When did you leave DC and why? Did you have any thoughts of returning? Or was this flight?

TSE: I didn’t want to leave. I left in 1986, to Boston/Cambridge––school, again and to become a writer or a filmmaker. I left for the bride of ideas. I left because I couldn’t get an apartment along the canal in Georgetown and because the city dug up the street in my neighborhood, Shaw, to insert train tracks and gray walls that we couldn’t. Flight, nope, I hate flying but I did feel the war zone of local progress (CHANGE) breathing down my neck.

I was reading a lot of Oscar Wilde then so there was no way I was going to buy or sell crack or get caught between those who were buying and selling crack. No way I was going to help with gentrification flight. The night Doug Williams raised his fist inside of his Redskins’ helmet, I was at the Chapter III listening to Little Benny and the Masters. I had my camera with me and Benny gave me the PA recording to take back to Cambridge with me.

E916: Where else have you lived? What impressions did these places leave on you?

TSE: The dull, metallic watercolors of Providence, Rhode Island for graduate school.

Boston – Haitians, Cape Verdians, Jamaicans and the intellectual interracial air traffic of progressive leisure. All I did was watch movies and write poems; be with black people. The whites were invisible to me.

Cleveland, where my funk matured and I learned to teach, my way,

and to interrupt my prose with lyric motion. The Sayers really started to show in my writing there. I was so bored I bought a Used SAAB (and drove to the Motown house/museum [in Detroit]) after swearing I’d never drive.

E16: I bought a copy of The Maverick Room . I’m enjoying it. On the cover is a photograph of what I believe is an alley community maybe in the old South West with the view of the Capitol dome in the background. When I read the caption, it said, “View of Slum Area with Capitol Building, 1940.” I guess the word “slum” pushed my button. I knew people from those alley neighborhoods, before they were razed during the urban renewal experiment in the 1950s. A lot of these people have passed on. I never recall thinking “slum,” although many of the alleys were. I do remember people who lived in them saying they’ve never felt any real connection to a community since leaving. Did you select this photo for the cover? If so, why or how does the photo work as a door to the poems in The Maverick Room? What community in DC do you still feel connected yet physically removed from?

TSE: I chose the photo.

I wished I had taken it.

I had it with me throughout High School taped inside my locker.

The view in the photo reminded me of the view of the Capitol Building from my grandmother house on Maryland Avenue (12 & F Streets, NE), and that’s where I was when Dr. King was killed, out front playing Dumb School on her steps as the noise and news rose up from H Street. All of my poems are noise and nuance. I got rid of the news. It wasn’t until I wrote “View of the Library of Congress from Paul Laurence Dunbar High School” that I realized that photo could serve, among other things, as a commentary of the tensions and distance between folk and political institutions, etc. Sadly, the photographer is unknown but the style has been passed on to me a bit, I believe, with my photography.

E916: What inspired you to take up photography?

TSE: Seeing things, blinking. Some desire to make a better memory than memory. “Shutters shut and shutters shut and so do queens.” That’s Gertrude Stein.

Both writing and photography seem incomplete to me without the other, no, it is me that seems incomplete without them.

The activity of them, in me, completes me.

E916: What kind of camera do you shoot with?

TSE: I use a Leica M7 and a Mamiya 7. I also have a Hasselblad 500 c/m.

E916: Do you prefer color or b&w?

TSE: I like both, but b/w prefers me. It’s always about Race.

E916: Digital, film or both? Do you have a preference?

TSE: I prefer film, the negative over the digital file, the image is textured differently to me.

But a good picture is a good picture. I am a manual man. All of the Go-Go Book is shot manually. I like focusing for myself. I like the mistakes.

E916: Did you mourn the death of Kodachrome this year? (Kodak discontinued the color film stock).

TSE: Suckas for real. They still haven’t invented a perfect film for black skin.

E916: You attended Paul Laurence Dunbar High School – not the “old Dunbar” as DC’s old timers say. Did you notice the difference? Did you think about the Duke Ellington School of the Arts or School Without Walls being that you were a creative?

TSE: I never thought about those schools. I was busy being percussive. I loved being in the Inner High, if not the public school system. There wasn’t an artist, in that way, in my life––and certainly not any middle class art or art-attitude. I knew the word aesthetics from Oscar Wilde and Soul from James Brown and that seemed a lot to me. “Bustin’ Loose” (Chuck Brown) had both and its own alphabet. “Roach ‘em on down.” As a matter of fact, I keep trying to write a poem called “Dear Don Cornelius” and I keep failing. I wrote poems at Dunbar too. I was a regular Lennon/McCartney, ha ha, but with a bass drum, some good ol’ bottom.

E916: I read your poem “View of the Library of Congress from Paul Laurence Dunbar High School” three times in the SE section of the book (The LOC is located in South East – Capitol Hill that is). For me it was a memory poem. I remember being introduced to Robert Hayden’s work in my teens during one of my summer job assignments (hat tip Marion Berry) at Howard University. I always felt he was one of those African American poets only English majors, Black Studies majors (maybe) and poets knew. That he got lost in the shuffle. Seems like Hayden was an epiphany? What makes Hayden special for you? If you were to select a Hayden poem or poems for classroom reading, what would it be?

TSE: I would select “American Journal,” some early Afrofuturism type throw down. Hayden, “an epiphany,” I don’t know. But I do know that I love his clock, the pacing of the thinking and feeling footsteps of his prosody, the way the writing is allowed breathing, his brand of care. He go slow and every syllable matters. I like that in the mind and in the mouth.

Young writers, like young drummers, think speed is King; nah Son. Pie are round, cornbread are square. Most spoken word artists rush the line and rush it with excess. Mouth, mouth, mouth. I’m just saying. Most academics drain the line, drain it with limitation. Mind, mind, mind. Perform-A-Forms don’t play that.

E916: As a poet, writer and photographer, you’re working in different genres and mediums. I’m also going to include musician since you were a percussionist. Do you find there’s a benefit in working in multiple disciplines, to not be boxed into just one thing? Perhaps it’s all relevant?

TSE: Wholeness is an advantage, a varied toolbox, but it is also very difficult to integrate styles and genres because you have to make them vanish into the object and you have to make new rules of behavior. A lot of DC artists do a lot of different things but they do not integrate them into a whole very well.

E916: What do you think of the arts scene or community in DC today compared to where it was in the mid to late 1970s and 1980s?

TSE: I don’t think about it. I know communities develop and under-redevlop in ebbs and flows. Institution building is tough. Everyone disagrees about the role of the artist in art, even the artist. The idea of local artist is a trap for some and a crown for others. The poet must be poetic and such comparisons are non-poetic–like comparing lengths of light or boiling a watch to see what makes it tick.

Be whole and alive in your age and brave and the past will pour what you need into you eliminating such questions. Also, the idea of thinking about time in terms of tens, of decades, that package, is such a dull and played repetitive ceiling.

E916: How important is it for an artist to be part of and active in a community? Artistic community or otherwise.

TSE: I think it’s important as pork. Seriously. Community happens in many ways. Internal ad external. It really depends on the quality of your imagination, what you are made of. You can be born with a connection to community in you or you can acquire one, and then there are many levels of in between. Tradition can be a blessing or a trap. Community too. The vessel I am likes the interaction but I have also seen too much interaction cause an artist to waste time and miss the boat and flood the craft. Either way Art marches on and either way we need exchange, folk to progress us.

E916: I’ve heard people say in New York you don’t have to justify art. You can do “art for art’s sake” and people accept it and fund it. They’ve also said in DC it’s harder to justify art unless there’s some educational, health, or sociological benefit? Since you’ve lived in both worlds, do you find that comparison is fair and accurate or is there a twist?

TSE: Both worlds have guidelines and governors and attitudes and amnesia and I am just a drum and no one really likes a drum, the constant banging all up in their face. If there is a twist, it’s population and agenda. It’s harder to see the limitations in NYC because of the number of people, while in DC the ups and downs and ins and outs of art commerce (the tastes and awards and networks) are more manageable, visually. It’s hard to hide the favors and it’s impossible not to notice that the fake DC favors imported-talent.

If I were from DC I’d move away, establish a name, then come back and run sh*t. I’d also stay away from the steps of the Senate in March because some of my new friends are now the enemies of the city.

E916: How is the Go-Go book coming along?

TSE: Go-Go keeps going. The book is always coming. I am reaching the point in it where I can see the people and the city change.

Time is beginning to enact width, range, purpose, on it.

I am patient.

Percussive too.

E916: What kind of footprint do you want the book to leave?

TSE: Folk shoes. A thumpin’ foot and a sock. I groove more than I crank.

E916: What happened to the Petworth Band you played in?

TSE: Band breakup. I still see them. It’s a long story that I just wrote and published in the new edition of “The Beat: Go-Go Music from Washington, DC” by Charles Stephenson and Kip Lornell. We played everywhere: the Howard Theater opening for Rare Essence, The Maverick Room, block parties, SYEP’s (Summer Youth Employment Program) Showmobile, high schools, Wilmer’s Park, The Moonlite Inn, Northwest Gardens, etc. I could go on.

I left Petworth for school and many of the other members stayed on and continue to play today in other bands. I photographed them in front of the remaining structure of the old O Street market last Spring.

E916: As a poet, writer and photographer, you’re working in different genres and mediums. I’m also going to include musician since you were a percussionist. Do you find there’s a benefit in working in multiple disciplines, to not be boxed into just one thing? Perhaps it’s all relevant?

TSE: Wholeness is an advantage, a varied toolbox, but it is also very difficult to integrate styles and genres because you have to make them vanish into the object and you have to make new rules of behavior. A lot of DC artists do a lot of different things but they do not integrate them into a whole very well. The amputation is thick there but a lot of DC artists are not from DC.

E916: Howard University gave birth to the “New Negro,” via philosophy professor Alain Locke. That thesis evolved into a “Harlem Renaissance.” Do you think Washington, DC is on the verge of something – another kind of Renaissance perhaps after the election of a Black President? [E916 note: Development in Harlem Renaissance history here.]

TSE: No. Nope

Go-Go is the only Artistic Independence Movement in DC.

Go-Go don’t know it though.

I’ve come to tell it.

No one wants to party with poor people.

Everyone else is just expressing themselves, everyone else has accepted their level in the hierarchy.

Not the drum.

The drum is might; the pocket, alphabet.

E916: Did you discover or reinvent any memorable third spaces, during your summer in DC, i.e. did you hang out and where?

TSE: I tried sitting on my mama’s porch with her more but the mosquitoes just kept coming. The most important part of my camera are my legs and they are extremely against first, second and third spaces. I try not to see closings or dead-end rooms. I fall the walls.

E916: Where and what in the fall?

TSE: I slave and I free, teaching “creative writing” (code term for courage), at Sarah Lawrence College. I also hand over, Skin, Inc., a new book of poems, to Graywolf Press, which will be out in Fall 2010. There’s even a reparations eye chart (in the form of a concrete poem) in it. I am all exclamation about this. I guess I am still teaching myself to see.